What action did Lincoln take to prevent Marylands secession?

Seal of Maryland during the war

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Maryland, a slave land, was i of the edge states, straddling the Due south and North. Despite some pop support for the crusade of the Confederate States of America, Maryland did not secede during the Civil War. Considering the state bordered the District of Columbia and the strong desire of the opposing factions within the state to sway public opinion towards their respective causes, Maryland played an important role in the war. Newly elected 16th President Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865, served 1861–1865), suspended the constitutional right of habeas corpus from Washington DC to Philadelphia, PA; and he dismissed Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (a Maryland native) of the U.Due south. Supreme Court's "Ex parte Merryman" determination in 1861 concerning freeing John Merryman, a prominent Southern sympathizer from Baltimore Canton arrested past the military machine and held in Fort McHenry (then nicknamed the "Baltimore Guardhouse"). The Chief Justice (not in a decision with the other justices) had held that the suspension was unconstitutional and could only be done by Congress and would leave lasting civil and legal scars.[one] The determination was filed in the U.S. Circuit Courtroom for Maryland by Master Justice Roger Brooke Taney, a Marylander from Frederick and one-time member of the assistants of the seventh President Andrew Jackson, who had nominated him ii decades earlier.

The get-go fatalities of the war happened during the Baltimore Civil War Riots of Th/Friday, April 18–19, 1861, on the waterfront piers next to Pratt and President Street, between the President Street Station and the Camden Street Station. A year and a one-half after, the single bloodiest day of combat in American armed forces history occurred during the first major Confederate invasion of the North in the Maryland Campaign, just n to a higher place the Potomac River about Sharpsburg in Washington Canton, at the Boxing of Antietam on September 17, 1862. Preceded by the pivotal skirmishes at 3 mount passes of Crampton, Fob and Turner'south Gaps to the e in the Battle of Southward Mount, Antietam (too known in the S as the Battle of Sharpsburg), though tactically a depict, was strategically enough of a Union victory in the second year of the war to give 16th President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity to upshot in September 1862, the Emancipation Proclamation, taking effect Jan 1, 1863, which alleged slaves in the rebelling states of the Confederacy (only non those in the areas already occupied by the Union Army or in edge slave states like Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri) to exist "henceforth and forever costless".

In July 1864 the Battle of Monocacy was fought near Frederick, Maryland as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Monocacy was a tactical victory for the Confederate States Army simply a strategic defeat, equally the one-24-hour interval delay inflicted on the attacking Confederates toll rebel General Jubal Early his gamble to capture the Union capital letter of Washington, D.C.

Beyond the state, some 50,000 citizens signed up for the armed services, with most joining the U.s.a. Ground forces. Approximately a tenth as many enlisted to "go South" and fight for the Confederacy. The most prominent Maryland leaders and officers during the Civil State of war included Governor Thomas H. Hicks who, despite his early sympathies for the South, helped prevent the state from seceding, and Confederate Brigadier General George H. Steuart, who was a noted brigade commander under Robert Eastward. Lee in the Ground forces of Northern Virginia.

Abolition of slavery in the State of Maryland came before the cease of the state of war, with a new third constitution voted approval in 1864 past a modest majority of Radical Republican Unionists then controlling the nominally Democratic country. Antagonism against Lincoln would remain, and Marylander John Wilkes Booth would electrocute President Lincoln on Apr xiv, 1865, then fleeing and hiding in southern Maryland for a week hunted by Federal troops before slipping beyond the Potomac and later shot in a Virginia barn.

The arroyo of War [edit]

Maryland's sympathies [edit]

8th Massachusetts regiment repairing railroad bridges from Annapolis to Washington.

Maryland, as a slave-belongings border state, was deeply divided over the antebellum arguments over states' rights and the future of slavery in the Marriage.[two] Culturally, geographically and economically, Maryland found herself neither one thing nor another, a unique blend of Southern agrarianism and Northern mercantilism.[ii] In the leadup to the American Civil War, it became clear that the state was bitterly divided in its sympathies. There was much less appetite for secession than elsewhere in the Southern States (S Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Alabama Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, Tennessee) or in the border states (Kentucky and Missouri),[3] but Maryland was equally unsympathetic towards the potentially abolitionist position of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln. In the presidential election of 1860 Lincoln won but 2,294 votes out of a total of 92,421, only 2.5% of the votes cast, coming in at a distant fourth identify with Southern Democrat (and after Confederate full general) John C. Breckinridge winning the state.[1] [4] In 7 counties, Lincoln received non a single vote.[ii]

The areas of Southern and Eastern Shore Maryland, especially those on the Chesapeake Bay (which neighbored Virginia), which had prospered on the tobacco trade and slave labor, were generally sympathetic to the Southward, while the primal and western areas of the state, especially Marylanders of German origin,[5] had stronger economical ties to the N and thus were pro-Union.[6] Not all blacks in Maryland were slaves. The 1860 Federal Census[7] showed there were virtually as many free blacks (83,942) as slaves (87,189) in Maryland, although the latter were much more dominant in southern counties.

Withal, beyond the land, sympathies were mixed. Many Marylanders were just businesslike, recognizing that the country's long border with the Spousal relationship state of Pennsylvania would exist almost impossible to defend in the issue of war. Maryland businessmen feared the likely loss of trade that would be caused past war and the stiff possibility of a blockade of Baltimore's port by the Union Navy.[8] Other residents, and a majority of the legislature, wished to remain in the Union, but did not want to be involved in a state of war confronting their southern neighbors, and sought to prevent a armed forces response by Lincoln to the South's secession.[9]

After John Brownish's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, many citizens began forming local militias, determined to prevent a future slave uprising.[ citation needed ]

Baltimore Riot of 1861 [edit]

The Baltimore Riot of Apr 1861

The first bloodshed of the Civil War occurred in Maryland. Anxious about the take a chance of secessionists capturing Washington, D.C., given that the uppercase was bordered by Virginia, and preparing for state of war with the South, the federal government requested armed volunteers to suppress "unlawful combinations" in the Southward.[ten] Soldiers from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts were transported past track to Baltimore, where they had to disembark, march through the city, and board another train to continue their journey due south to Washington.[11]

As ane Massachusetts regiment was transferred between stations on April 19, a mob of Marylanders sympathizing with the South, or objecting to the employ of federal troops confronting the seceding states, attacked the train cars and blocked the road; some began throwing cobblestones and bricks at the troops, assaulting them with "shouts and stones".[12] Panicked past the state of affairs, several soldiers fired into the mob, whether "accidentally", "in a desultory manner", or "past the command of the officers" is unclear.[12] Chaos ensued equally a behemothic brawl began between fleeing soldiers, the trigger-happy mob, and the Baltimore police who tried to suppress the violence. Four soldiers and twelve civilians were killed in the anarchism.

The disorder inspired James Ryder Randall, a Marylander living in Louisiana, to write a verse form which would be put to music and, in 1939, become the state song, "Maryland, My Maryland" (it remained the official state vocal until March 2021). The song's lyrics urged Marylanders to "spurn the Northern scum" and "burst the tyrant'south chain" — in other words, to secede from the Union. Confederate States Army bands would later play the vocal after they crossed into Maryland territory during the Maryland Entrada in 1862.[xiii]

Afterward the April 19 rioting, skirmishes continued in Baltimore for the next calendar month. Mayor George William Chocolate-brown and Maryland Governor Thomas Hicks implored President Lincoln to reroute troops around Baltimore city and through Annapolis to avoid further confrontations.[14] In a letter of the alphabet to President Lincoln, Mayor Brown wrote:

It is my solemn duty to inform yous that it is not possible for more than soldiers to pass through Baltimore unless they fight their way at every stride. I therefore promise and trust and nearly earnestly request that no more troops be permitted or ordered by the Government to pass through the city. If they should endeavour it, the responsibleness for the bloodshed will not balance upon me.[14]

Hearing no immediate reply from Washington, on the evening of April nineteen Governor Hicks and Mayor Brown ordered the destruction of railroad bridges leading into the city from the North, preventing further incursions by Union soldiers. The destruction was achieved the next day.[15] I of the men involved in this devastation would be arrested for it in May without recourse to habeas corpus, leading to the ex parte Merryman ruling. For a fourth dimension it looked as if Maryland was one provocation away from joining the rebels, but Lincoln moved swiftly to defuse the state of affairs, promising that the troops were needed purely to defend Washington, not to attack the South.[16] President Lincoln as well complied with the asking to reroute troops to Annapolis, as the political situation in Baltimore remained highly volatile. Meanwhile, General Winfield Scott, who was in charge of war machine operations in Maryland indicated in correspondence with the head of Pennsylvania troops that the road through Baltimore would resume one time sufficient troops were available to secure Baltimore.[17]

To secede or not to secede [edit]

Despite some popular support for the cause of the Amalgamated States of America, Maryland did non secede during the Civil War. Yet, a number of leading citizens, including md and slaveholder Richard Sprigg Steuart, placed considerable pressure on Governor Hicks to summon the state Legislature to vote on secession, following Hicks to Annapolis with a number of fellow citizens:

to insist on his [Hicks] issuing his announcement for the Legislature to convene, believing that this trunk (and not himself and his party) should decide the fate of our state...if the Governor and his party continued to refuse this demand that it would be necessary to depose him.[eighteen]

Responding to pressure level, on April 22 Governor Hicks finally announced that the land legislature would meet in a special session in Frederick, a strongly pro-Union town, rather than the state upper-case letter of Annapolis. The Maryland Full general Assembly convened in Frederick and unanimously adopted a measure out stating that they would not commit the country to secession, explaining that they had "no constitutional authorisation to have such activity,"[19] any their own personal feelings might have been.[twenty] On April 29, the Legislature voted decisively 53–13 against secession,[21] [22] though they also voted not to reopen track links with the Northward, and they requested that Lincoln remove Matrimony troops from Maryland.[23] At this time the legislature seems to have wanted to avert involvement in a war confronting its southern neighbors.[24]

Imposition of martial law [edit]

Cannon on Federal Loma, aimed at downtown Baltimore

On May 13, 1861 General Benjamin F. Butler entered Baltimore by rail with 1,000 Federal soldiers and, under encompass of a thunderstorm, quietly took possession of Federal Hill.[8] Butler fortified his position and trained his guns upon the city, threatening its destruction.[25] Butler then sent a letter to the commander of Fort McHenry:

I have taken possession of Baltimore. My troops are on Federal Hill, which I tin hold with the help of my artillery. If I am attacked to-dark, please open upon Monument Foursquare with your mortars.[26]

Butler went on to occupy Baltimore and declared martial law, ostensibly to preclude secession, although Maryland had voted solidly (53–xiii) confronting secession two weeks before,[27] merely more than immediately to allow war to be made on the South without hindrance from the state of Maryland,[25] which had too voted to close its rail lines to Northern troops, and so every bit to avert interest in a war against its southern neighbors.[28] By May 21 there was no need to transport further troops.[25] Later the occupation of the urban center, Union troops were garrisoned throughout the state. By tardily summertime Maryland was firmly in the hands of Matrimony soldiers. Arrests of Confederate sympathizers and those critical of Lincoln and the state of war soon followed, and Steuart'south brother, the militia general George H. Steuart, fled to Charlottesville, Virginia, subsequently which much of his family's property was confiscated by the Federal Government.[29] Ceremonious authority in Baltimore was swiftly withdrawn from all those who had non been steadfastly in favor of the Federal Authorities's emergency measures.[xxx]

During this period in spring 1861, Baltimore Mayor Brown,[31] the metropolis council, the police force commissioner, and the unabridged Board of Police, were arrested and imprisoned at Fort McHenry without charges.[one] [32] One of those arrested was militia captain John Merryman, who was held without trial in disobedience of a writ of habeas corpus on May 25, sparking the instance of Ex parte Merryman, heard just 2 days subsequently May 27 and 28. In this example U.S. Supreme Courtroom Main Justice, and native Marylander, Roger B. Taney, acting as a federal excursion courtroom gauge, ruled that the abort of Merryman was unconstitutional without Congressional authorization, which Lincoln could not then secure:

The President, under the Constitution and laws of the United States, cannot suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, nor authorize whatsoever military officeholder to do so.[33]

The Merryman decision created a awareness, but its immediate impact was rather limited, as the president simply ignored the ruling.[34] Indeed, when Lincoln'south dismissal of Chief Justice Taney'due south ruling was criticized in a September 1861 editorial past Baltimore newspaper editor Frank Key Howard (Francis Scott Key's grandson), Howard was himself arrested by gild of Lincoln's Secretarial assistant of State Seward and held without trial. Howard described these events in his 1863 book Fourteen Months in American Bastiles, where he noted that he was imprisoned in Fort McHenry, the same fort where the Star Spangled Banner had been waving "o'er the country of the free" in his grandfather's vocal.[35] Two of the publishers selling his book were then arrested.[one] In all ix newspapers were close down in Maryland by the federal regime, and a dozen newspaper owners and editors like Howard were imprisoned without charges.[ane]

On September 17, 1861, the get-go day of the Maryland legislature's new session, fully 1 third of the members of the Maryland General Assembly were arrested, due to federal concerns that the Associates "would assist the anticipated insubordinate invasion and would endeavour to take the country out of the Union."[36] Although previous secession votes, in leap 1861, had failed by large margins,[22] in that location were legitimate concerns that the war-averse Assembly would farther impede the federal government's use of Maryland infrastructure to wage state of war on the South.

I month later in October 1861 one John Murphy asked the United states of america Circuit Court for the District of Columbia to event a writ of habeas corpus for his son, then in the United States Army, on the grounds that he was underage. When the writ was delivered to General Andrew Porter Provost Align of the Commune of Columbia he had both the lawyer delivering the writ and the United states Circuit Judge, Marylander William Matthew Merrick, who issued the writ, arrested to forbid them from proceeding in the case United states ex rel. Murphy five. Porter. Merrick's fellow judges took up the case and ordered Full general Porter to announced before them, just Lincoln'southward Secretary of Land Seward prevented the federal marshal from delivering the court guild.[37] The court objected that this disruption of its process was unconstitutional, but noted that information technology was powerless to enforce its prerogatives.[38] [39]

The following calendar month in November 1861, Judge Richard Bennett Carmichael, a presiding state circuit court judge in Maryland, was imprisoned without charge for releasing, due to his concern that arrests were capricious and civil liberties had been violated, many of the southern sympathizers seized in his jurisdiction. The order came over again from Lincoln'due south Secretary of State Seward. The federal troops executing Judge Carmichael'southward arrest beat him unconscious in his courthouse while his court was in session, before dragging him out, initiating a public controversy.[40]

In another controversial arrest that autumn, and in further defiance of Chief Justice Taney's ruling, a sitting U.Due south. Congressman Henry May (D-Maryland) was imprisoned without charge and without recourse to habeas corpus in Fort Lafayette.[41] [42] May was eventually released and returned to his seat in Congress in Dec 1861, and in March 1862 he introduced a pecker to Congress requiring the federal government to either indict by thousand jury or release all other "political prisoners" still held without habeas.[43] The provisions of May'due south bill were included in the March 1863 Habeas Corpus Act, in which Congress finally authorized Lincoln to suspend habeas corpus, only required bodily indictments for suspected traitors.[44]

Marylanders fought both for the Marriage and the Confederacy [edit]

Although Maryland stayed as function of the Spousal relationship and more Marylanders fought for the Union than for the Confederacy, Marylanders sympathetic to the secession easily crossed the Potomac River into secessionist Virginia in order to join and fight for the Confederacy. During the early summer of 1861, several thousand Marylanders crossed the Potomac to bring together the Amalgamated Regular army. Well-nigh of the men enlisted into regiments from Virginia or the Carolinas, but six companies of Marylanders formed at Harpers Ferry into the Maryland Battalion.[45] Amidst them were members of the quondam volunteer militia unit, the Maryland Baby-sit Battalion, initially formed in Baltimore in 1859.[46]

Maryland Exiles, including Arnold Elzey and brigadier full general George H. Steuart, would organize a "Maryland Line" in the Regular army of Northern Virginia which somewhen consisted of ane infantry regiment, one infantry battalion, two cavalry battalions and four battalions of arms.[ citation needed ] Most of these volunteers tended to hail from southern and eastern counties of the state, while northern and western Maryland furnished more volunteers for the Marriage armies.[47]

Captain Bradley T. Johnson refused the offer of the Virginians to bring together a Virginia Regiment, insisting that Maryland should be represented independently in the Amalgamated army.[45] It was agreed that Arnold Elzey, a seasoned career officer from Maryland, would command the 1st Maryland Regiment. His executive officeholder was the Marylander George H. Steuart, who would afterward be known as "Maryland Steuart" to distinguish him from his more famous cavalry colleague J.East.B. Stuart.[45]

The 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment was officially formed on June 16, 1861, and, on June 25, two boosted companies joined the regiment in Winchester.[45] Its initial term of duty was for twelve months.[48]

Information technology has been estimated that, of the country'southward 1860 population of 687,000, about four,000 Marylanders traveled south to fight for the Confederacy. While the number of Marylanders in Confederate service is oftentimes reported as 20-25,000 based on an oral argument of General Cooper to General Trimble, other contemporary reports refute this number and offer more than detailed estimates in the range of 3,500 (Livermore)[49] to just nether iv,700 (McKim),[50] which latter number should be further reduced given that the second Maryland Infantry raised in 1862 consisted largely of the same men who had served in the 1st Maryland, which mustered out later a year.

While other men built-in in Maryland may have served in other Confederate formations, the same is true of units in the service of the Us. The 1860 Demography reported the chief destinations of internal immigrants from Maryland as Ohio and Pennsylvania, followed by Virginia and the Commune of Columbia.[51]

A similar situation existed in relation to Marylanders serving in the U.s.a. Colored Troops. Indeed, on the whole at that place appear to have been twice every bit many blackness Marylanders serving in the U.S.C.T. as white Marylanders in the Amalgamated army.[52]

Overall, the Official Records of the War Department credits Maryland with 33,995 white enlistments in volunteer regiments of the U.s.a. Regular army and 8,718 African American enlistments in the United States Colored Troops. A further 3,925 Marylanders, not differentiated by race, served as sailors or marines.[53] One notable Maryland front line regiment was the 2nd Maryland Infantry, which saw considerable combat action in the Union Ix Corps. Another was the 4th Usa Colored Troops, whose Sergeant Major, Christian Fleetwood was awarded the Medal of Honor for rallying the regiment and saving its colors in the successful attack on New Market place Heights.[54]

A country divided [edit]

Not all those who sympathised with the rebels would carelessness their homes and join the Confederacy. Some, like physician Richard Sprigg Steuart, remained in Maryland, offered covert support for the South, and refused to sign an adjuration of loyalty to the Union.[55] Later in 1861, Baltimore resident W W Glenn described Steuart as a fugitive from the authorities:

I was spending the evening out when a pace approached my chair from backside and a hand was laid upon me. I turned and saw Dr. R. South. Steuart. He has been concealed for more than six months. His neighbors are so biting confronting him that he dare not go habitation, and he committed himself then incomparably on the 19th April and is known to exist so decided a Southerner, that it more than probable he would be thrown into a Fort. He goes most from place to place, sometimes staying in one canton, sometimes in another and then passing a few days in the city. He never shows in the day time & is cautious who sees him at any time.[56]

Civil War [edit]

Battle of Front Royal [edit]

Crossing the Potomac into Maryland on 6th September 1862

Because Maryland'south sympathies were divided, many Marylanders would fight i another during the disharmonize. On May 23, 1862, at the Battle of Front end Royal, the 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA was thrown into battle with their young man Marylanders, the Spousal relationship 1st Regiment Maryland Volunteer Infantry.[45] This is the only fourth dimension in United States armed forces history that two regiments of the same numerical designation and from the same country take engaged each other in boxing.[57] After hours of desperate fighting the Southerners emerged victorious, despite an inferiority both of numbers and equipment.[57] When the prisoners were taken, many men recognized onetime friends and family. Major William Goldsborough, whose memoir The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army chronicled the story of the rebel Marylanders, wrote of the battle:

most all recognized sometime friends and acquaintances, whom they greeted cordially, and divided with them the rations which had simply changed hands.[58]

Amid the prisoners captured by William Goldsborough was his own brother Charles Goldsborough.[59]

On 6 September 1862 advancing Confederate soldiers entered Frederick, Maryland, the abode of Colonel Bradley T. Johnson, who issued a proclamation calling upon his boyfriend Marylanders to join his colors. Disappointingly for the exiles, recruits did not flock to the Amalgamated banner. Whether this was due to local sympathy with the Matrimony cause or the generally ragged state of the Confederate regular army, many of whom had no shoes, is not clear.[5] Frederick would afterwards be extorted by Jubal Early on, who threatened to burn downwardly the metropolis if its residents did not pay a bribe.[lx] Hagerstown too would as well suffer a like fate.[61]

"Encarmine Antietam" [edit]

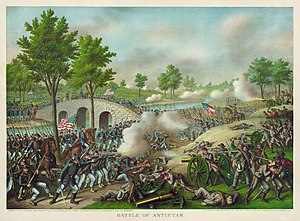

Battle of Antietam past Kurz and Allison.

Confederate dead at Antietam.

1 of the bloodiest battles fought in the Civil war (and one of the most significant) was the Battle of Antietam, fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, in which Marylanders fought with stardom for both armies.[62] The battle was the culmination of Robert E. Lee's Maryland Campaign, which aimed to take the war to the North. Lee'southward Army of Northern Virginia, consisting of about 40,000 men, had entered Maryland following their recent victory at Second Bull Run.[63]

While Major General George B. McClellan's 87,000-man Regular army of the Potomac was moving to intercept Lee, a Spousal relationship soldier discovered a mislaid copy of the detailed battle plans of Lee'southward army, on Sunday 14 September.[62] The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically (to Harpers Ferry, W Virginia, and Hagerstown, Maryland), thus making each subject to isolation and defeat in detail - if McClellan could move quickly enough.[62] However, McClellan waited about 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence and position his forces based on information technology, thus endangering a aureate opportunity to defeat Lee decisively.[64]

The armies met most the town of Sharpsburg by the Antietam Creek. Losses were extremely heavy on both sides; The Marriage suffered 12,401 casualties with 2,108 expressionless. Amalgamated casualties were 10,318 with 1,546 dead. This represented 25% of the Federal force and 31% of the Confederate. More Americans died in battle on September 17, 1862, than on any other mean solar day in the nation's armed forces history. The Confederate General A. P. Hill described

the virtually terrible slaughter that this war has even so witnessed. The wide surface of the Potomac was blue with floating bodies of our foe. Merely few escaped to tell the tale.[65]

Although tactically inconclusive, the Battle of Antietam is considered a strategic Wedlock victory and an important turning betoken of the state of war, because information technology forced the end of Lee'southward invasion of the North, and it allowed President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, taking consequence on January i, 1863. Lincoln had wished to issue his proclamation earlier, but needed a military victory in order for his announcement not to become self-defeating. Equally Lincoln himself stated, v days before the boxing:

What good would a proclamation from me practice.... I don't want to result a certificate the whole globe volition see must be inoperative, like the Pope'south Bull against a comet.[66]

Lee's setback at the Battle of Antietam can also be seen as a turning bespeak in that it may accept dissuaded the governments of French republic and Great Great britain from recognizing the Confederacy, doubting the South's ability to maintain and win the war.[67]

March to Gettysburg [edit]

The Confederate 2d Maryland infantry charge Spousal relationship lines at Gettysburg

In June 1863 General Lee's army again avant-garde northward into Maryland, taking the war into Matrimony territory for the 2d fourth dimension. Maryland exile George H. Steuart, leading the 2nd Maryland Infantry regiment, is said to have jumped down from his equus caballus, kissed his native soil and stood on his head in jubilation. According to one of his aides: "We loved Maryland, we felt that she was in bondage against her will, and we burned with desire to take a part in liberating her".[68] Quartermaster John Howard recalled that Steuart performed "seventeen double somersaults" all the while whistling Maryland, My Maryland.[69] Such celebrations would bear witness brusk lived, as Steuart's brigade was soon to be severely damaged at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–three, 1863), a turning point in the state of war and a reverse from which the Confederate army would never recover.

Battle of Monocacy [edit]

In 1864, elements of the warring armies again met in Maryland, although this time the scope and size of the battle was much smaller. The Boxing of Monocacy was fought on July 9, just outside Frederick, as function of the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early defeated Union troops nether Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace. The boxing was part of Early on's raid through the Shenandoah Valley and into Maryland, attempting to divert Marriage forces away from Gen. Robert Due east. Lee's army under siege at Petersburg, Virginia. However, Wallace delayed Early on for nearly a full twenty-four hour period, buying enough time for Ulysses Due south. Grant to send reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac to the Washington defenses.[ citation needed ]

Prisoners of state of war [edit]

Thousands of Union troops were stationed in Charles County, and the Federal Government established a large, unsheltered prison camp at Bespeak Lookout at Maryland's southern tip in St. Mary's Canton between the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay, where thousands of Confederates were kept, often in harsh weather condition. Of the 50,000 Southern soldiers held in the army prison house camp, who were housed in tents at the Indicate between 1863 and 1865, co-ordinate to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, (Maryland Park Service) about four,000 died, although this death charge per unit of eight percent was less than half the death rate among soldiers who were however fighting in the field with their own armies.[70] The harshness of weather at Betoken Spotter, and in particular whether such weather condition formed part of a deliberate policy of "vindictive directives" from Washington, is a affair of some debate.[71]

The state capital letter Annapolis's western suburb of Parole became a camp where prisoners-of-state of war would wait formal commutation in the early on years of the war. Effectually lxx,000 soldiers passed through Camp Parole until Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant causeless control as Full general-in-Chief of the Matrimony Army in 1864, and ended the arrangement of prisoner exchanges.[72]

Slavery and emancipation [edit]

Those who voted for Maryland to remain in the Union did not explicitly seek for the emancipation of Maryland's many enslaved people, or indeed those of the Confederacy. In March 1862, the Maryland Assembly passed a series of resolutions, stating that:

This war is prosecuted by the Nation with merely one object, that, namely, of a restoration of the Union just equally it was when the rebellion bankrupt out. The rebellious States are to be brought back to their places in the Union, without change or diminution of their constitutional rights.[73]

In other words, the Assembly members could only concur to state that the war was beingness fought over the issue of secession. Because Maryland had not seceded from the United States the state was not included under the Emancipation Proclamation of January one, 1863, which declared that all enslaved people within the Confederacy would henceforth be gratuitous. In 1864, before the stop of the State of war, a constitutional convention outlawed slavery in Maryland.

Constitution of 1864, and the abolition of slavery [edit]

The effect of slavery was finally confronted by the constitution which the country adopted in 1864. The document, which replaced the Maryland Constitution of 1851, was largely advocated by Unionists who had secured command of the state, and was framed by a Convention which met at Annapolis in April 1864.[74] Article 24 of the constitution at last outlawed the exercise of slavery.

I feature of the new constitution was a highly restrictive oath of allegiance which was designed to reduce the influence of Southern sympathizers, and to prevent such individuals from holding public function of whatever kind.[74] The new constitution emancipated the state'south slaves (who had not been freed by President Lincoln'south Emancipation Proclamation), disenfranchised southern sympathizers, and re-apportioned the General Assembly based upon white inhabitants.[ citation needed ] This last provision diminished the power of the minor counties where the bulk of the country's large former slave population lived.

The constitution was submitted to the people for ratification on October 13, 1864 and information technology was narrowly approved past a vote of 30,174 to 29,799 (50.31% to 49.69%) in a vote probable overshadowed by the heavy presence of Union troops in the state and the repression of Amalgamated sympathizers.[75] Those voting at their usual polling places were opposed to the Constitution by 29,536 to 27,541.[ citation needed ] Nonetheless, the constitution secured ratification one time the votes of Union army soldiers from Maryland were included.[75] The Marylanders serving in the Union Regular army were overwhelmingly in favor of the new Constitution, supporting ratification by a margin of 2,633 to 263.[75]

The new constitution came into result on November 1, 1864 and, while it emancipated the state's slaves, it did not mean equality for them, in part because the franchise continued to exist restricted to white males. The abolitionism of slavery in Maryland preceded the Thirteenth Subpoena to the Us Constitution outlawing slavery throughout the United States and did not come up into effect until December six, 1865. Maryland had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment on February iii, 1865, within three days of it existence submitted to the states.

Emancipation did not immediately bring citizenship for onetime slaves. The Maryland legislature refused to ratify both the 14th Subpoena, which conferred citizenship rights on former slaves, and the 15th Amendment, which gave the vote to African Americans.[ citation needed ]

The right to vote was eventually extended to not-white males in the Maryland Constitution of 1867, which remains in event today. The Constitution of 1867 overturned the registry test adjuration embedded in the 1864 constitution.

Assassination of President Lincoln [edit]

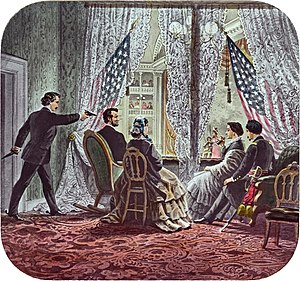

Marylander John Wilkes Booth assassinates President Lincoln

The issue of slavery may have been settled by the new constitution, and the legality of secession past the war, simply this did not end the debate. On April 14, 1865 the role player John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. After he shot Lincoln, Berth shouted "Sic semper tyrannis" ("Thus always to tyrants").[76] Other witnesses — including Booth himself — claimed that he only yelled "Sic semper!"[77] [78] Some didn't recall hearing Booth shout anything in Latin. Some witnesses said he shouted "The South is avenged!"[79] : 48 Others thought they heard him say "Revenge for the South!" or "The South shall be free!" Two said Booth yelled "I have done it!" Later shooting the President, Booth galloped on his equus caballus into Southern Maryland, where he was sheltered and helped by sympathetic residents and smuggled at night across the Potomac River into Virginia a calendar week later on.

In a letter of the alphabet explaining his actions, Berth wrote:

I accept always held the South was correct. The very nomination of Abraham Lincoln, four years agone, spoke plainly war upon Southern rights and institutions... And looking upon African Slavery from the aforementioned stand-point held by the noble framers of our constitution, I for one, have ever considered it ane of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and united states of america,) that God has always bestowed upon a favored nation… I have as well studied difficult to discover upon what grounds the correct of a Land to secede has been denied, when our very proper noun, United States, and the Declaration of Independence, both provide for secession.[80]

Legacy [edit]

Most Marylanders fought for the Matrimony, simply after the war a number of memorials were erected in sympathy with the Lost Crusade of the Confederacy, including in Baltimore a Amalgamated Women's Monument, and a Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Baltimore boasted a monument to Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson[81] until they were taken down on August 16, 2017.[82] A home for retired Confederate soldiers in Pikesville, Maryland opened in 1888 and did non close until 1932. A brochure published past the home in the 1890s described it every bit:

a haven of rest... to which they may retire and notice refuge, and, at the aforementioned time, lose none of their cocky-respect, nor suffer in the estimation of those whose experience in life is more fortunate.[83]

There is a Confederate monument backside the courthouse in Rockville, Maryland, dedicated to "the thin grey line".[84] Easton, Maryland also has a Confederate monument.[85] A statue of General Robert Eastward. Lee in Baltimore was recently removed.[ when? ] Maryland has three chapters of the Sons of Amalgamated Veterans.

War produced a legacy of bitter resentment in politics, with the Democrats beingness identified with "treason and rebellion", a point much pressed home past their opponents.[86] Democrats therefore re-branded themselves the "Autonomous Bourgeois Party", and Republicans called themselves the "Wedlock" party, in an attempt to distance themselves from their most radical elements during the war.[86]

The legacies of the debate over Lincoln'south heavy-handed actions that were meant to keep Maryland inside the marriage include measures such every bit arresting one third of the Maryland Full general Assembly, which was controversially ruled unconstitutional at the time by Maryland native Justice Roger Taney, and in the lyrics of the erstwhile Maryland state vocal, Maryland, My Maryland, which referred to Lincoln as a "autocrat," a "vandal," and, a "tyrant."

Run into also [edit]

- History of slavery in Maryland

- History of the Maryland Militia in the Civil State of war

- List of Maryland Union Ceremonious State of war units

- Listing of Maryland Confederate Ceremonious State of war units

- Maryland Line (CSA)

References [edit]

- Andrews, Matthew Page, History of Maryland, Doubleday, New York (1929)

- Arnett, Robert J., et al., Maryland: A New Guide to the Old Line Country The Johns Hopkins University Press (1999)

- Davis, David Brion, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World Retrieved January 2013

- Back-scratch, Denis, C., "Native Maryland, 9000 B.C.–1600 A.D." (2001). Retrieved August 2012

- Gallagher, Gary W., Antietam: Essays on the 1862 Maryland Campaign, Kent Country Academy Press (31 December 1992) Retrieved Jan 2013

- Gillipsie, James M., Andersonvilles Of The Due north: The Myths and Realities of Northern Treatment of Civil War Amalgamated Prisoners, University of Due north Texas Press (2011) Retrieved January 2013

- Goldsborough, W. West., The Maryland Line in the Amalgamated Army, Guggenheimer Weil & Co (1900), ISBN 0-913419-00-1.

- Harris, William C. (2011) Lincoln and the Border States: Preserving the Wedlock. University Printing of Kansas.

- Hein, David (editor),. Religion and Politics in Maryland on the Eve of the Civil War: The Letters of W. Wilkins Davis. 1988. Rev. ed., Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2009.

- Maryland State Athenaeum (16 Sept. 2004).Historical Chronology Retrieved August 2012.

- Mitchell, Charles West., Maryland Voices of the Ceremonious State of war. Retrieved Baronial 2012

- Scharf, J. Thomas (1967 (reissue of 1879 ed.)). History of Maryland From the Earliest Period to the Nowadays 24-hour interval. 3. Hatboro, PA: Tradition Press

- Scharf, J. Thomas, History of Western Maryland: Beingness a History of Frederick, Montgomery, Carroll, Washington, Allegany, and Garrett Counties. (1882) Retrieved November 2012

- Tagg, Larry, The Generals of Gettysburg, Savas Publishing (1998), ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Whitman H. Ridgway. Maryland Humanities Council (2001). "(Maryland in) the Nineteenth Century". Retrieved August 2012

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d e Schoettler, Carl (November 27, 2001). "A time liberties weren't priority". The Baltimore Lord's day . Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Charles (ed.). Maryland Voices of the Civil War. p. 3.

- ^ Andrews, p506

- ^ Andrews, p.505

- ^ a b Andrews, p. 539

- ^ Field, Ron, et al., p.33, The Confederate Army 1861–65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved August 2012

- ^ 1860 Census Information, U.Due south. Census Bureau

- ^ a b Mitchell, p.12 Retrieved November 2012

- ^ "Didactics American History in Maryland – Documents for the Classroom: Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861". Maryland State Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on Jan 11, 2008. Retrieved Feb half dozen, 2008.

- ^ Andrews, p.511

- ^ Andrews, p.512

- ^ a b Andrews, p.514

- ^ Scharf, J. Thomas (1967) [1879]. "History of Maryland From the Earliest Flow to the Present Solar day". iii. Hatboro, PA: Tradition Press: 494.

- ^ a b Andrews, p.517

- ^ Harris (2011) pp. 46-47

- ^ Andrews, p.518

- ^ Harris (2011) pp. 51-52. Harris states that Lincoln may or may non have been enlightened of this communication.

- ^ Mitchell, p.71

- ^ Scharf, p.202 Retrieved November 2012

- ^ Andrews, p.520

- ^ Mitchell, p.87

- ^ a b Radcliffe, George Lovic-Pierce, Governor Thomas H. Hicks of Maryland and the Civil War, The Johns Hopkins Press, Nov-December 1901, pp. 73-74.

- ^ "Teaching American History in Maryland – Documents for the Classroom: Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861". Maryland Land Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved Feb half-dozen, 2008.

- ^ "Teaching American History in Maryland – Documents for the Classroom: Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861". Maryland Country Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c Andrews, p.521

- ^ Maryland Historical Society Retrieved Feb 2013

- ^ "States Which Seceded". eHistory. Civil War Articles. Ohio State University. Archived from the original on October six, 2014. Retrieved October xvi, 2014.

- ^ "Education American History in Maryland – Documents for the Classroom: Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861". Maryland State Athenaeum. 2005. Archived from the original on Jan xi, 2008. Retrieved Feb vi, 2008.

- ^ Brugger, Robert J., Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634–1980. p.280 Retrieved Feb 28 2010

- ^ Andrews, p.524

- ^ Mitchell, p.207

- ^ Mitchell, p.291 Retrieved Nov 2012

- ^ Andrews, p.523

- ^ Andrews, p.522

- ^ Howard, F. K. (Frank Central) (1863). Xiv Months in American Bastiles. London: H. F. Mackintosh. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ William C. Harris, Lincoln and the Border States: Preserving the Matrimony (Academy Press of Kansas, 2011) pp.71

- ^ Inside Lincoln's White Business firm: The Consummate Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 28 (SIU Printing, Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger eds. 1999).

- ^ 12 Stat. 762.

- ^ "History of the Federal Judiciary: Circuit Courtroom of the District of Columbia: Legislative History". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Scharf, J. Thomas. "Suspension of Civil Liberties in Maryland". Maryland Country Athenaeum. Archived from the original on May xix, 2008. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ^ The Bastille in America; or Democratic Absolutism. London: Robert Hardwicke, 1861, p. 12.

- ^ Mitchell, Charles Westward., ed. Maryland Voices of the Civil State of war. JHU Printing, 2007, p. 237.

- ^ Jonathan White, "Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil State of war: The Trials of John Merryman", LSU Press, 2011. p. 106

- ^ Jonathan White, "Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman", LSU Press, 2011. p. 107

- ^ a b c d e "2nd Maryland Infantry, CSA". Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ Field, Ron, et al., The Confederate Regular army 1861–65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved March 4, 2010

- ^ Andrews, p.543

- ^ Andrews, p.544

- ^ Thomas Livermore, Numbers and Losses in the Civil State of war, Boston, 1900. Run into chart and explanation, p. 550

- ^ Randolph McKim, Numerical Force of the Confederate Army, New York, 1912. See discussion and tabulation on pp. 62-65. Of the Trimble count, McKim states The estimate to a higher place alluded to, of 20,000 Marylanders in the Confederate service, rests apparently upon no better basis than an oral statement of General Cooper to General Trimble, in which he said he believed that the muster rolls would show that almost 20,000 men in the Amalgamated ground forces had given the Land of Maryland as the place of their nascence. How many were citizens of Maryland when they enlisted does not appear. Obviously many natives of Maryland were doubtless in 1861 citizens of other States, and could not therefore be reckoned among the soldiers furnished by Maryland to the Confederate armies.

- ^ Population of the U.s. in 1860, 1000.P.O. 1864. See Introduction, p. xxxiv

- ^ See, east.yard., C. R. Gibbs' Blackness, Copper, and Brilliant, Silver Spring, Maryland, 2002. This history of the 1st U.S.C.T., credited to the District of Columbia contains roster on pp. 228-259 list more than 300 men built-in in Maryland. Similarly, Robert Beecham, in his memoir, As If It Were Glory, Lanham, Maryland, 1998, p. 166, says of the 23rd UsC.T. that "the 23rd was fabricated up of men generally from Washington and Baltimore" though the regiment was credited to the state of Virginia.

- ^ The War of the Rebellion, Serial III, Volume 4, pp. 69-lxx.

- ^ William A. Dobak, Freedom past the Sword, Skyhorse Publishing, 2013

- ^ Helsel, David S., p.xix, Jump Grove State Hospital Retrieved February 26, 2010

- ^ Mitchell, Charles West., p.285, Maryland Voices of the Civil State of war Retrieved Feb 26, 2010

- ^ a b Andrews, p.531

- ^ Goldsborough, J. J., p.58, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army Retrieved May thirteen, 2010

- ^ Goldsborough, West.Due west., Introduction, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Ground forces, Butternut Printing, Maryland (1983)

- ^ Loewen, James W. (July 1, 2015). "Why do people believe myths about the Confederacy? Because our textbooks and monuments are wrong. Fake history marginalizes African Americans and makes us all dumber". The Washington Mail . Retrieved March 10, 2016.

Confederate cavalry leader Jubal Early demanded and got $300,000 from them lest he burn down their town, a sum equal to at to the lowest degree $5,000,000 today.

- ^ "Hagerstown Herald and Torch Light". Western Maryland Historical Library. July 20, 1864. Retrieved January ane, 2014.

- ^ a b c Andrews, p.541

- ^ Andrews, p.539

- ^ McPherson, p. 109.

- ^ Andrews, p.542

- ^ Davis, p.313 Retrieved January 2013

- ^ Gallagher, p.vii Retrieved January 2013

- ^ Tagg, p.273

- ^ Goldsborough, p.98.

- ^ Point Watch History, Maryland Department of Natural Resources Retrieved August 2012

- ^ Gillipsie, p.179 Retrieved January 2013

- ^ Arnett, p.81 Retrieved January 2013

- ^ Andrews, p.527

- ^ a b Andrews, p.553

- ^ a b c Andrews, p.554

- ^ "Diary Entry of John Wilkes Booth".

- ^ Diary Entry of John Wilkes Booth Archived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ "TimesMachine April 15, 1865 - New York Times". The New York Times.

- ^ Swanson, James. Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Harper Collins, 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-051849-3

- ^ "The murderer of Mr. Lincoln" (PDF). The New York Times. April 21, 1865.

- ^ "Lee-Jackson Memorial" Smithsonian Art Inventories Catalog Retrieved May 2013

- ^ Welsh, Sean; Campbell, Colin (August 16, 2017). "Confederate monuments taken down in Baltimore overnight". The Baltimore Sunday . Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ Maryland Historical Club Retrieved January 2013

- ^ www.waymarking.com Rockville Civil War Monument - Rockville, Maryland. Retrieved August 2012

- ^ Campbell, Colin (May 16, 2016). "Equally Confederate symbols come down, 'Talbot Boys' endures". The Baltimore Sun . Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Andrews, p.563

Further reading [edit]

- Bakery, Jean H. The Politics of Continuity: Maryland Political Parties from 1858 to 1870 (Johns Hopkins UP, 1973) online.

- Fields, Barbara. Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Basis: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (1987).

External links [edit]

- National Park Service map of Civil War sites in Maryland

- Maryland War machine Historical Society

- American Ceremonious War: Maryland Resources

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maryland_in_the_American_Civil_War

0 Response to "What action did Lincoln take to prevent Marylands secession?"

Post a Comment