Peer Reviewed Journal Article Related to an Ethical Issue in Sport

- Current Stance

- Open up Access

- Published:

Mental Health In Aristocracy Athletes: Increased Awareness Requires An Early Intervention Framework to Respond to Athlete Needs

Sports Medicine - Open book five, Article number:46 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

The electric current 'country of play' in supporting elite athlete mental health and wellbeing has centred mostly on building mental health literacy or sensation of the signs of mental ill-health amid athletes. Such sensation is necessary, but not sufficient to address the varied mental health needs of aristocracy athletes. Nosotros call for a new model of intervention and outline the courage of a comprehensive mental wellness framework to promote athlete mental wellness and wellbeing, and respond to the needs of athletes who are at-risk of developing, or already experiencing mental wellness symptoms or disorders. Early detection of, and intervention for, mental health symptoms is essential in the elite sporting context. Such approaches help build cultures that admit that an athlete's mental health needs are as important as their physical wellness needs, and that both are likely to contribute to optimising the athlete's overall wellbeing in conjunction with performance excellence. The proposed framework aims at (i) helping athletes develop a range of self-direction skills that they tin can utilise to manage psychological distress, (ii) equipping key stakeholders in the elite sporting environment (such as coaches, sports medicine and high-performance support staff) to better recognise and reply to concerns regarding an athlete's mental health and (iii) highlighting the need for specialist multi-disciplinary teams or skilled mental health professionals to manage athletes with severe or complex mental disorders. Combined, these components ensure that elite athletes receive the intervention and support that they need at the correct fourth dimension, in the correct place, with the right person.

Key Points

-

Currently, there is no comprehensive framework or model of intendance to back up and respond to the mental health needs of elite athletes.

-

We suggest a framework that recognises the impact of general and athlete-specific risk factors, and engages fundamental individuals that may identify and promote athlete mental wellness.

-

The framework is adjustable and responsive to varied career stages and mental health states.

There has been a rapid increase in research examining the mental health of aristocracy athletes culminating with the International Olympic Committee's (IOC's) recent Expert Consensus Statement on mental health in elite athletes [1]. This statement provides a comprehensive analysis of, and recommendations for, the treatment of both high prevalence (e.g. feet and mood symptoms) and more complex mental health disorders (e.g. eating and bipolar disorders) in the elite sporting context. This is a timely resources which will aid guide and ultimately amend the clinical management of athletes by sports medicine, mental wellness, and allied wellness professionals. The primary focus of the consensus argument, along with much of the extant literature, is on managing the individual athlete affected by mental sick-health. There has been little scholarly and service-level attention to more than comprehensive frameworks that (a) recognise the office of the broader aristocracy sports ecology as both a contributor to athlete mental wellness difficulties and a facilitator of their remediation, and (b) approaches that emphasise the prevention of mental wellness symptoms, along with early detection and intervention to restore athlete wellbeing (and ideally optimise operation).

Take a chance Factors for Mental Ill-health in Elite Athletes

Meta-analytic reviews indicate that elite athletes feel broadly comparable rates of mental ill-health relative to the general population in relation to feet, depression, mail-traumatic stress and sleep disorders [2, 3]. This should not be unexpected given the considerable overlap in the years of active aristocracy competition and the chief ages of onset for well-nigh mental disorders [4,v,half-dozen].

Increasing evidence points to a range of both athlete-specific and general adventure factors associated with mental sick-health in elite athletes. Athlete-specific hazard indicators include sports-related injury and concussion [iii, 7,8,nine], performance failure [x], overtraining (and overtraining syndrome) [xi] and sport type (e.1000. individual sports conferring a college take a chance that squad sports) [12]. General adventure indicators include major negative life events [thirteen, 14], low social back up [xv, 16] and dumb sleep [17, xviii]. These take chances factors may affect the severity and onset of detail mental health symptoms, but can besides guide appropriate response strategies.

The salience of particular risk factors may vary beyond career phases. For case, in junior evolution years, supportive relationships with parents and coaches are imperative to athlete wellbeing [xix, twenty]. During the high performance and elite phase, in addition to the coaching relationship, environmental and training demands become more relevant to mental health and wellbeing [21], including extended travel away from dwelling house and exposure to unfamiliar (training) environments [22]. Environmental conditions and travel may be especially salient for the mental wellness of para-athletes, who often encounter disruptive logistical problems associated with travel, such equally a lack of adaptive sport facilities and sleeping weather [23]. Prominent adventure factors during the transition out of sport include involuntary or unplanned retirement and lack of a non-athletic identity, both of which are associated with a range of psychological challenges [24]. For para-athletes, involuntary retirement due to declassification (i.eastward. no longer coming together the required criteria to be classified as a para-athlete) is a unique burden [25].

Optimising the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Elite Athletes: Barriers and Facilitators

A comprehensive framework for mental health in elite athletes needs to consider the range of relevant risk factors across key career phases, equally well as factors that inhibit or facilitate the power to effectively respond to athletes' needs. Primal barriers include more than negative attitudes towards assist-seeking amongst athletes than the general population [26], as well as greater stigma and poorer mental health literacy. Fear of the consequences of seeking aid (e.grand. loss of option) and lack of time are also influential [26,27,28]. Facilitative factors include support and acknowledgment from coaches [27] who tin assistance to create a non-stigmatised environs where help-seeking can be normalised [28]. Approaches that seek to optimise athletic performance while simultaneously providing intervention for mental health symptoms may also facilitate engagement [29, 30]. Brief anti-stigma interventions and mental health literacy programs that seek to increase cognition of mental health symptoms have been shown to improve assist-seeking intentions in elite athletes [31,32,33], although the touch of such programs on help-seeking behaviours is not known.

Are in that location Existing Frameworks or Models of Care for Mental Health in Elite Sport?

To date at that place are no published frameworks regarding how best to support the mental health needs of elite athletes. In addition to the IOC Consensus Argument, recent position statements have emphasised the demand to build sensation of mental health issues and increase assistance-seeking behaviours [34,35,36]. These initiatives are unquestionably warranted; however, improving awareness and aid-seeking behaviours are at best pointless, and at worst unsafe, if systems of care to respond to athlete's demand are not available. A whole of system approach needs to be developed simultaneously.

Across the peer-reviewed literature, useful guidelines be within selected sporting associations regarding supporting athlete wellbeing [37,38,39]. These resources highlight a number of disquisitional factors in managing athlete mental health in the sporting context including (i) the sports' responsibleness for managing the athlete's intendance and support (e.g. duty of care issues); (ii) the need for regular screening or monitoring of athletes to detect changes in mental state or behaviour; (iii) privacy and confidentiality regarding mental health as key ethical issues and challenges; (iv) athlete preferences for help-seeking (how and from whom); (v) the need to refer out to or engage external mental wellness professionals where expertise does not exist inside the sporting environment; and (vi) the value of trained peer workers (one-time athletes/players) to provide support and guidance to athletes and to coordinate activities related to professional person development needs (such as public speaking or fiscal planning) and private goal-setting (due east.g. effectually educational or post-sport vocational interests). Yet, no single framework incorporates all of these factors nor is there a framework that focuses on the spectrum of athlete/player mental wellness needs, from symptom prevention to specialist mental wellness care. There has been some progress in developing mental wellness guidelines in collegiate-level athletes [40,41,42], which highlight the demand to provide specific and targeted back up, while noting that few comprehensive or targeted models of intendance for mental health accept been developed for this population.

Developing a Comprehensive Mental Health Framework to Support Elite Athletes

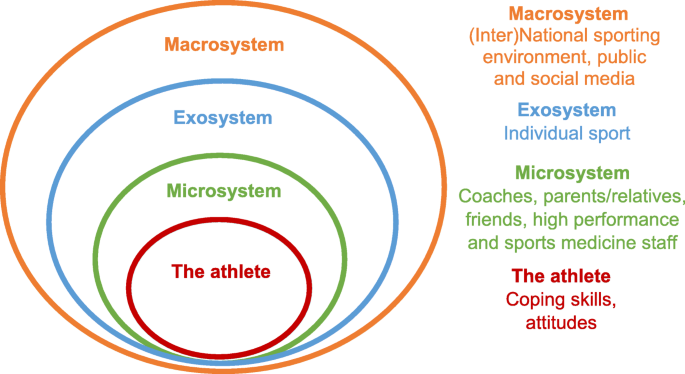

Many of the full general and athlete-specific risk factors for mental ill-wellness are potentially modifiable (e.1000. coping strategies, coaching manner, training demands) and require intervention at the individual athlete, the sporting or ecology and/or organisational levels. A comprehensive framework for athlete mental wellness that is conceptualised within the broader 'ecology' of elite sporting environments will be best able to reply to the range of take chances indicators in this context (run across Fig. i). Ecological systems help to explain the relationship between the aspects or experiences of an individual (termed 'ontogenetic' factors, such equally coping or substance use) and the broader social and cultural contexts in which they be [43]. In the case of aristocracy athletes, this includes the 'microsystem' of double-decker(es), teammates (where advisable) and family/loved ones. The wider sporting environment (due east.grand. the athlete'due south sport, its rules and governing body) forms the exosystem, while the role of national and international sporting bodies and the media and broader gild class the macrosystem.

An ecological systems model for elite athlete mental health

Any mental health framework that ignores wider ecological factors runs the chance of focusing exclusively on, and potentially pathologising the private athlete, when other factors may exist more influential in contributing to, or perpetuating poor mental health. Such factors may include maladaptive relationships with coaches or parents, social media abuse and/or financial pressures.

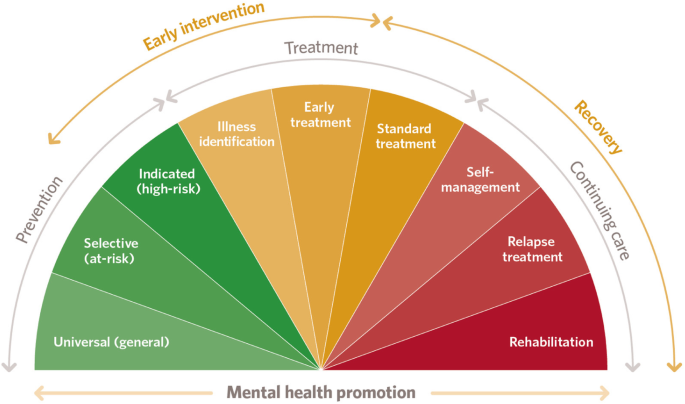

In addition to ecological factors, a comprehensive framework for mental health should cover both prevention and early intervention, consequent with established models that are influential in public health and social policy (e.g. Haggerty and Mrazek'south mental wellness promotion spectrum [44]; see Fig. 2). An early intervention framework can optimise athlete mental wellbeing and respond rapidly to mental health symptoms and disorders as they emerge to all-time maintain the athlete'due south overall office.

The mental health promotion spectrum

Inside this framework, the prevention stages aim to reduce the risk of mental wellness symptoms developing or to minimise their potential touch on and severity; the handling and early on intervention stages seek to place and halt the progression of emerging mental health difficulties; and the standing care stages help an individual to recover and prevent relapse, typically through ongoing clinical intendance with a mental wellness professional [44].

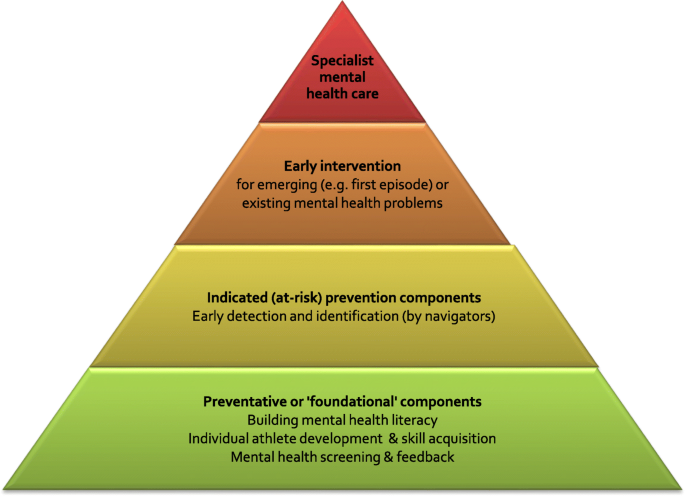

Based on the extant literature regarding hazard factors for mental ill-wellness in elite athletes, along with existing sporting guidelines or statements regarding athlete wellbeing, and our experience developing and implementing early on intervention services and system reform for immature people's mental health [45,46,47], nosotros suggest the post-obit framework to respond to the mental health of elite athletes (see Fig. iii).

Elite athlete mental wellness and wellbeing framework

Preventative or 'Foundational' Components

Core foundational components should include (i) mental health literacy to improve understanding, reduce stigma and promote early help-seeking; (ii) a focus on athlete development (both career and personal evolution goals) and skill acquisition to aid attain these goals; and (3) mental health screening of, and feedback to, athletes. The purpose of these foundational components is to raise awareness of the importance of athlete wellbeing across the aristocracy sport 'environmental'. This in turn addresses workplace duty of care and occupational health and rubber responsibilities towards athletes' overall wellbeing in the context of sport-related stressors.

Mental Wellness Literacy

Mental health literacy programs should be provided to athletes, coaches and loftier-performance back up staff to help to create a culture that values enhancing the mental health and wellbeing of all stakeholders. Programs should also be offered to the athlete'south family or friends to build their chapters to place symptoms and encourage help-seeking, specially as these are the individuals from whom athletes volition initially seek help and support [48, 49]. Engaging an array of individuals, including organisational staff, in these programs broadens the attain of mental health literacy within an athlete's (or sport's) ecology (see Fig. 1). Gulliver and colleagues effectively trialled the delivery of a mental health literacy program to elite athletes via team-based workshops facilitated by mental health professionals [26]. This delivery method is preferred given the opportunity for qualified facilitators to discuss and explore athlete questions or concerns (especially regarding confidentiality and the implications of help-seeking for selection) and to potentially problem-solve together. The content of such preparation should be customised to address the specific aspects of the sport (e.g. team-based versus private sport) and developmental stages (e.grand. junior versus retiring athletes). Basic program content should encompass (i) athlete-specific and general risk factors that can increase susceptibility to mental ill-health; (ii) key signs or symptoms of impaired wellbeing; (iii) how and from whom to seek assistance, both inside and outside the sport; and (iv) bones techniques for athletes to self-manage transient mood states or psychological distress, such every bit relaxation techniques, adaptive coping strategies, self-pity and mindfulness.

Individually Focused Development Programs

Individually focused evolution programs can assist athletes to identify personal/vocational goals and acquire the skills necessary to reach them. This is necessary to help develop a parallel not-athletic identity, the skills to manage life-sport balance and to set up for the eventual end of competitive sport. The latter may be challenging in younger athletes who ofttimes lack the longer-term perspective or life experience to perceive the need for such planning. However, a focus on developing a non-athletic identity must occur at all phases of the sporting career and non be confined to the transition out of sport phase, since edifice such skills takes time (and athletes are prone to unplanned retirement due to injury). These activities are ideally facilitated by a skilled, well-trained 'peer workforce'. These are individuals who have a lived experience of mental ill-wellness and sufficient training to share their knowledge to assistance support others in similar situations [50]. In the sporting context, a peer workforce could include erstwhile athletes or coaches who work with current athletes to discuss and normalise experiences of mental health symptoms or their run a risk factors. Sometime athletes can assist with athlete development programs and mobilise athletes to the importance of actively participating with such programs, based on their own experiences [39].

Mental Wellness Screening

Mental health screening should be included alongside routine concrete wellness checks by medical staff as part of a comprehensive framework. Screening items should exist sensitive to the elite context [fifty, 51] and should be designed to provide feedback to athletes to help promote improved self-awareness, such equally their mental land and triggers for symptoms. Critical times to screen are following severe injury (including concussion) and during the transition into, and out of sport [ane], and the lead-upwards to and mail major competitions may also be periods of college risk. It is important to note that at that place is currently a lack of widely validated athlete-specific screening tools, though i elite athlete sensitised screening measure—the Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire—has been validated in a big sample of male aristocracy athletes reporting potent psychometric properties [52], and is nether farther validation with female and inferior athletes. Research potential exists to not just develop further athlete-specific measures, but to determine who is all-time suited to conduct screening, and what credentials or grooming may be required to ensure safe and integrity in this process (e.g. that appropriate help or referral is provided to athletes who screen positive).

Indicated ('at-risk') Prevention Programs

The 2d phase is indicated prevention programs for those considered or assessed every bit existence 'at-risk' of dumb mental health and wellbeing. This phase aims to mitigate the likelihood of deterioration in mental health past detecting symptoms every bit early as possible and facilitating referral to appropriate health professionals. Key staff within the sports organization tin can be assisted to develop skills in early symptom identification and to promote professional help-seeking. This includes coaches, athletic trainers and teammates (where appropriate) who are in a position to detect 'micro' changes in an athlete over days or weeks, and sports medicine staff, such equally physiotherapists who may detect other non-appreciable signs, such as changes in energy or body tension. We term these individuals 'navigators' in the mental health framework, as they have a crucial office in observing the athlete's behaviour or mental state and being able to link them to professional care. These navigators tin be provided with additional grooming (adjunctive to mental health literacy) to better recognise and interpret the athlete'south behaviour in relation to their overall wellbeing, understand athlete privacy concerns that inhibit the disclosure of mental wellness symptoms and build self-efficacy to exist able to raise their concerns safely with the affected athlete or medical/mental wellness staff.

Sport administrators should also consider developing guides on 'what to do if concerned about an athlete'due south mental wellbeing' and make these available to all relevant staff. These should include data regarding appropriate referral sources, responses (e.1000. prevention program vs. early intervention) and facilitators to engage athletes, such as support and encouragement [27, 28] and/or linking mental wellbeing with athletic performance [29, xxx]. Protocols or guides for responding to mental health concerns become less stigmatised when wellbeing needs are already routinely promoted via foundational programs.

Early Intervention

Early intervention is necessary in instances where the performance and life demands placed on an athlete exceed their ability to cope (i.due east. major career-threatening injury or significant life stress). Structured clinical interventions for mild to moderate mental ill-health are typically indicated at this phase and should ideally be provided 'in-house' by mental health clinicians, such every bit sports or clinical psychologists or psychiatrists, or medical staff where appropriate (eastward.g. pharmacotherapy). The use of in-house professionals helps to counter the depression levels of service use associated with referring athletes out to external service providers and the stigma that is associated with the athlete needing expert 'exterior assist' [53]. Where requisite in-house expertise does not exist, this can be managed past the employ of qualified consultants, but ideally these professionals should be 'embedded' to some extent inside the sporting environment to ensure that athletes and other staff understand 'who they are and what their role is', even if their presence is infrequent [54]. When referral out is necessary, or preferred by the athlete, ideally this should be to a mental health professional with appropriate sport sensitised training, knowledge and experience assisting aristocracy athletes.

Early interventions need not always be confront-to-face, just can be augmented by telephone or web-enabled consultations, the latter particularly relevant given the frequency with which elite athletes travel unaccompanied by the sporting entourage. All interventions, regardless of the mode of delivery, should utilize an individualised care approach that is based on assessment and conceptualisation of the individual athlete's presenting problem(s). The intervention should target the psychological processes of the athlete that are impeding mental health [55] and accept account of the specific familial, sporting and organisational issues that may be impacting on the athlete's wellbeing.

An example of an early intervention model of care is the Australian Constitute of Sport (AIS) mental wellness referral network [56]. Athletes are assessed past an AIS mental health advisor, who can make a referral, if necessary, to a qualified mental wellness practitioner who has been credentialed to work inside the network. This practitioner so works individually with the athlete to address their needs and ideally restore their mental health and functioning [57].

Specialist Mental Health Care

Despite best efforts to prevent or intervene early, some athletes will nonetheless experience astringent or complex psychopathology requiring specialist mental health care, specially where there is a risk of harm to self or others. In some cases, this may include hospitalisation or specialist inpatient or day programs. The IOC Good Consensus Argument provides a summary of recommended clinical interventions for a range of mental disorders, including bipolar, psychotic, eating and depressive disorders, and suicidality [one]. Developing and implementing a mental health emergency program may too exist required, particularly in cases where an athlete presents with an acute disturbance in their mental state, for instance agitation/paranoia, or suicidal ideation [58]. The IOC Expert Consensus Argument recommends that structured plans should admit and define what constitutes a mental wellness emergency, identify which personnel (or local emergency services) are contacted and when, and consider relevant mental health legislation [i].

There is also arguably a need for 'return to sport or training' guidance for athletes who have been unable to compete or train for their sport due to mental illness, alike to guidelines for managing concussion [59]. Such guidance could potentially provide a graduated, stride-past-step protocol that prepares non only the athlete for a successful render to sport, but also the microsystem that supports them.

Conclusions

We have proposed a comprehensive framework for elite athlete mental health. More than research is needed to eternalize the efficacy of the approaches discussed here in the aristocracy sports context, equally well as other factors that are nether-researched in the literature, such equally gender-specific considerations in mental health [60] and considerations for para-athletes [23]. We are mindful that coaches and other loftier-performance staff are vulnerable to mental health problems [61] and the needs of these individuals need to be incorporated into a more inclusive model of care. Further, we recognise the scope of this framework does non cover the needs of non-elite athletes. Elements of this framework may exist tailored in the future to be applicable and contextualised for non-aristocracy environments where in that location may exist limited resources, less professional staffing and greater limitations in athlete schedules.

Despite the exponential increase in research interest related to athlete mental wellbeing, major service delivery and treatment gaps remain. Evaluating the efficacy of mental health prevention and intervention programs via controlled trials or other high-quality designs is urgently needed. Program evaluation should ideally adopt an ecological systems approach to account for contest-related, individual-vulnerability and organisational factors on mental wellness outcomes, for example by seeking to mensurate system-level variables (east.g. the caste of perceived psychological condom inside the sporting organisation [62, 63]) and individual athlete-level variables (e.g. coping skills, relationship with bus, injury history). As initiatives are evaluated and enhanced or adapted, developers should consult with elite sport organisations and individuals to ensure the relevance and sport sensitivity of their programs. Increased resource and enquiry funding to support the evaluation and implementation of athlete mental health programs is needed, such as currently exists for managing athletes' physical health (e.g. musculoskeletal injuries, concussion).

Finally, we are acutely enlightened that a framework such as that articulated here requires substantial investment and that such funding is scant even in high income settings. The foundational and at-risk components lend themselves, we believe, to be adaptable to depression resource settings, given the emphasis on athlete self-direction and a trained peer workforce. Adaptations to providing early intervention in low resource settings will be needed, and innovations in general mental health can act as a blueprint [64]. Regardless of settings or resources, investment in a comprehensive response to athlete mental health needs attending if information technology is to ever gain parity with physical health.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IOC:

-

International Olympic Committee

- AIS:

-

Australian Institute of Sport

References

-

Reardon CL, Hainline B, Aron CM, Businesswoman D, Baum AL, Bindra A, et al. Mental health in aristocracy athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53(eleven):667–99. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715.

-

Gouttebarge 5, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gorczynski P, Hainline B, Hitchcock ME, Kerkhoffs GM, et al. Occurrence of mental wellness symptoms and disorders in current and former aristocracy athletes: a systematic review and meta-assay. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53(11):700–vi.

-

Rice SM, Gwyther One thousand, Santesteban-Echarri O, Baron D, Gorczynski P, Gouttebarge V, et al. Determinants of feet in aristocracy athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53(xi):722–30.

-

Rice SM, Purcell R, De Silva South, Mawren D, McGorry PD, Parker AG. The mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review. Sports Med. 2016;46(ix):1333–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-ii.

-

Allen SV, Hopkins WG. Historic period of peak competitive performance of elite athletes: a systematic review. Sports Medicine. 2015;45(ten):1431–41.

-

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-4 disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of full general psychiatry. 2005;62(half dozen):593–602.

-

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Mackinnon A, Batterham PJ, Stanimirovic R. The mental health of Australian aristocracy athletes. Journal of scientific discipline and medicine in sport. 2015;18(3):255–61.

-

Peluso MAM, Andrade LHSGd. Physical activity and mental health: the association between practice and mood. Clinics. 2005;60(1):61-70.

-

Rice SM, Parker AG, Rosenbaum South, Bailey A, Mawren D, Purcell R. Sport-related concussion and mental health outcomes in elite athletes: a systematic review. Sports medicine. 2018;48(ii):447–65.

-

Hammond T, Gialloreto C, Kubas H, Davis HH Iv. The prevalence of failure-based depression among elite athletes. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2013;23(4):273–7.

-

Frank R, Nixdorf I, Beckmann J. Depression amidst aristocracy athletes: prevalence and psychological factors. Deut Z Sportmed. 2013;64:320–6.

-

Schaal 1000, Tafflet M, Nassif H, Thibault V, Pichard C, Alcotte M, et al. Psychological balance in high level athletes: gender-based differences and sport-specific patterns. PLoS I. 2011;half dozen(v):e19007. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pone.0019007.

-

Nixdorf I, Frank R, Hautzinger M, Beckmann J. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and correlating variables amid German elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2013;7(4):313–26.

-

Gouttebarge 5, Aoki H, Verhagen EA, Kerkhoffs GM. A 12-month prospective accomplice study of symptoms of mutual mental disorders amid European professional person footballers. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2017;27(five):487–92.

-

Gutmann MC, Pollock ML, Foster C, Schmidt D. Training stress in Olympic speed skaters: a psychological perspective. The Doctor and Sportsmedicine. 1984;12(12):45–57.

-

Kotnik B, Tušak M, Topič MD, Leskošek B. Some psychological traits of Slovene Olympians (Beijing 2008)—a gender comparison. Kinesiologia Slovenica. 2012;xviii(two).

-

Gupta L, Morgan G, Gilchrist South. Does aristocracy sport degrade sleep quality? A systematic review. Sports Medicine. 2017;47(7):1317–33.

-

Kölling S, Steinacker JM, Endler South, Ferrauti A, Meyer T, Kellmann M. The longer the better: sleep–wake patterns during grooming of the globe rowing inferior championships. Chronobiology international. 2016;33(1):73–84.

-

Berntsen H, Kristiansen Eastward. Guidelines for Need-Supportive Motorcoach Development: The Motivation Activation Program in Sports (MAPS). International Sport Coaching Journal. 2019;6(ane):88–97.

-

Sabato TM, Walch TJ, Caine DJ. The elite young athlete: strategies to ensure concrete and emotional wellness. Open admission periodical of sports medicine. 2016;seven:99.

-

Saw AE, Master LC, Gastin PB. Monitoring the athlete grooming response: subjective self-reported measures trump usually used objective measures: a systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;50(5):281–91. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094758.

-

Donnelly AA, MacIntyre TE, O'Sullivan N, Warrington G, Harrison AJ, Igou ER, et al. Environmental influences on aristocracy sport athletes well being: from gold, silverish, and bronze to blue green and gold. Frontiers in psychology. 2016;7:1167.

-

Swartz L, Chase Ten, Bantjes J, Hainline B, Reardon CL. Mental wellness symptoms and disorders in Paralympic athletes: a narrative review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019:bjsports-2019-100731.

-

Knights S, Sherry E, Ruddock-Hudson M. Investigating aristocracy finish-of-able-bodied-career transition: a systematic review. Periodical of Applied Sport Psychology. 2016;28(3):291–308.

-

Bundon A, Ashfield A, Smith B, Goosey-Tolfrey VL. Struggling to stay and struggling to leave: The experiences of elite para-athletes at the end of their sport careers. Psychology of Sport and Do. 2018;37:296–305.

-

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young aristocracy athletes: a qualitative study. BMC psychiatry. 2012;12(i):157.

-

Castaldelli-Maia JM. Gallinaro JGdMe, Falcão RS, Gouttebarge V, Hitchcock ME, Hainline B et al. Mental health symptoms and disorders in elite athletes: a systematic review on cultural influencers and barriers to athletes seeking treatment. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53(11):707–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100710.

-

Reardon CL, Factor RM. Sport psychiatry: A systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Medicine. 2010;twoscore(11):961–eighty.

-

Donohue B, Gavrilova Y, Galante M, Gavrilova E, Loughran T, Scott J, et al. Controlled evaluation of an optimization arroyo to mental health and sport performance. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2018;12(ii):234–67.

-

Gavrilova Y, Donohue B, Galante M. Mental wellness and sport performance programming in athletes who present without pathology: A case test supporting optimization. Clinical Case Studies. 2017;sixteen(iii):234–53.

-

Bapat S, Jorm A, Lawrence K. Evaluation of a mental health literacy grooming program for junior sporting clubs. Australasian psychiatry. 2009;17(6):475–ix.

-

Beauchemin J. College student-athlete wellness: An integrative outreach model. College Educatee Periodical. 2014;48(ii):268–80.

-

Kern A, Heininger Westward, Klueh E, Salazar S, Hansen B, Meyer T, et al. Athletes connected: results from a airplane pilot projection to accost knowledge and attitudes most mental health among college pupil-athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2017;xi(4):324–36.

-

Henriksen G, Schinke R, Moesch Thou, McCann S, Parham William D, Larsen CH, et al. Consensus statement on improving the mental wellness of loftier performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2019:ane–viii. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473.

-

Moesch K, Kenttä Chiliad, Kleinert J, Quignon-Fleuret C, Cecil Southward, Bertollo M. FEPSAC position statement: mental health disorders in aristocracy athletes and models of service provision. Psychology of Sport and Do. 2018.

-

Schinke RJ, Stambulova NB, Si Grand, Moore Z. International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes' mental wellness, functioning, and development. International journal of sport and exercise psychology. 2018;16(vi):622–39.

-

Queensland University of Sport. Athlete wellbeing framework. Queensland Academy of Sport, https://www.qasport.qld.gov.au/about/documents/qas-athlete-wellbeing-framework.pdf. 2014. Accessed twenty May 2019.

-

Lomax L. System recognises importance of support to help athletes with mental wellness bug. English Establish of Sport, https://www.eis2win.co.britain/2014/08/21/system-recognises-importance-support-assist-athletes-mental-wellness-problems/. 2014. .

-

Australian Football game League Players' Clan. Evolution and wellbeing study 2014. Australian football game league players' association, http://www.aflplayers.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Dev-Wellbeing-2015.pdf. 2014. Accessed 20 May 2019.

-

Brown GT, Hainline B, Kroshus E, Wilfert 1000. Mind, body and sport: agreement and supporting student-athlete mental wellness. IN: NCAA: Indianapolis; 2014.

-

Neal TL, Diamond AB, Goldman S, Klossner D, Morse ED, Pajak DE, et al. Inter-association recommendations for developing a program to recognize and refer student-athletes with psychological concerns at the collegiate level: an executive summary of a consensus argument. Journal of Able-bodied Training. 2013;48(5):716–twenty.

-

Thompson R, Sherman R. Managing student-athletes' mental wellness bug. National Collegiate Athletic Association: Indianapolis; 2007.

-

Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1992.

-

Haggerty RJ, Mrazek PJ. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention enquiry: National Academies Printing; 1994.

-

Purcell R, Goldstone S, Moran J, Albiston D, Edwards J, Pennell K, et al. Toward a Xx-First Century Approach to Youth Mental Health Care. International Journal of Mental Health. 2011;forty(2):72–87. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMH0020-7411400204.

-

McGorry PD, Purcell R, Goldstone Due south, Amminger GP. Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental and substance apply disorders: implications for preventive intervention strategies and models of care. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2011;24(4):301–half-dozen.

-

Rice SM, Purcell R, McGorry PD. Adolescent and young adult male mental health: transforming organisation failures into proactive models of engagement. Periodical of Adolescent Wellness. 2018;62(3):S9–S17.

-

Pierce D, Liaw S-T, Dobell J, Anderson R. Australian rural football club leaders every bit mental wellness advocates: an investigation of the touch of the Coach the Passenger vehicle projection. International journal of mental health systems. 2010;4(1):x.

-

Naoi A, Watson J, Deaner H, Sato M. Multicultural bug in sport psychology and consultation. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2011;nine(2):110–25.

-

Vandewalle J, Debyser B, Beeckman D, Vandecasteele T, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S. Peer workers' perceptions and experiences of barriers to implementation of peer worker roles in mental health services: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2016;60:234–l.

-

Donohue B, Galante G, Hussey J, Lee B, Paul N, Perry JE, et al. Empirical Development of a Screening Method to Assist Mental Wellness Referrals in Collegiate Athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 2019:ane–28. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2018-0070.

-

Rice SM, Parker AG, Mawren D, Clifton P, Harcourt P, Lloyd M, et al. Preliminary psychometric validation of a cursory screening tool for athlete mental wellness among male person elite athletes: the Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire. International Journal of Sport and Practice Psychology. 2019:1–16.

-

McDuff DR. Sports psychiatry: strategies for life residual and pinnacle functioning. American Psychiatric Pub; 2012.

-

Morse ED. Sports Psychiatrists Working in College Athletic Departments. Clinical Sports Psychiatry. 1988;203.

-

Moore ZE, Bonagura K. Electric current opinion in clinical sport psychology: from athletic operation to psychological well-existence. Current opinion in psychology. 2017;16:176–nine.

-

Australian Institute of Sport. Mental health referral network: Back up for elite AIS-funded athletes with mental wellness concerns. SportAus, https://www.sportaus.gov.au/ais/MHRN. 2018. Accessed xx May 2019.

-

Rice Southward, Butterworth K, Clements Thou, Josifovski D, Arnold S, Schwab C, et al. Development and implementation of the national mental health referral network for elite athletes: A example study of the Australian Plant of Sport. Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology. Under review. .

-

Currie A, McDuff D, Johnston A, Hopley P, Hitchcock ME, Reardon CL et al. Management of mental wellness emergencies in elite athletes: a narrative review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019:bjsports-2019-100691. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-100691.

-

McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Bailes J, Broglio South, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(xi):838–47.

-

Rice SM, Fallon BJ, Aucote HM, Möller-Leimkühler AM. Evolution and preliminary validation of the male low risk scale: Furthering the cess of depression in men. Journal of affective disorders. 2013;151(three):950–viii.

-

Carson F, Walsh J, Main LC, Kremer P. High operation coaches' mental health and wellbeing: Applying the areas of work life model. International Sport Coaching Journal. 2018;5(iii):293–300.

-

Spink KS, Wilson KS, Brawley LR, Odnokon P. The perception of team envrionment: The relationship between the psychological climate and members' perceived effort in high-functioning groups. Grouping Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Do. 2013;17(3):150–61.

-

Stachan L, Côté J, Deakin J. A new view: Exploring positive youth evolution in aristocracy sport contexts. Qualitative Inquiry in Sport, Exercise and Wellness. 2011;3(1):nine–32.

-

Chibanda D, Weiss HA, Verhey R, Simms 5, Munjoma R, Rusakaniko S, et al. Effect of a primary care–based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2016;316(24):2618–26.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Simon M Rice was supported past a Career Development Fellowship (APP115888) from the National Wellness and Medical Research Council.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

RP and SMR made substantial contributions to the conception of the manuscript. RP, KG and SMR drafted, revised and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ideals Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicative.

Competing Interests

The authors, Rosemary Purcell, Kate Gwyther, and Simon 1000. Rice, declare that they accept no competing interests relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Purcell, R., Gwyther, K. & Rice, South.Grand. Mental Health In Elite Athletes: Increased Awareness Requires An Early Intervention Framework to Respond to Athlete Needs. Sports Med - Open up five, 46 (2019). https://doi.org/x.1186/s40798-019-0220-1

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-019-0220-1

Source: https://sportsmedicine-open.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40798-019-0220-1

0 Response to "Peer Reviewed Journal Article Related to an Ethical Issue in Sport"

Post a Comment